the liberalization of India's economy in 1991 marked the beginning of a significant shift. By the early 2000s, the top 1% controlled more than 15% of the national income. By the time Modi took office in 2014, this figure had crossed 20%, and by 2022-2023, it had soared to an unprecedented 22.6%. While India's GDP continues to grow at over 7% annually, this rapid economic expansion seems to exacerbate the inequality, creating a scenario where the rich are getting richer at an unprecedented pace

In 2014, Narendra Modi’s ascent to power marked a significant transformation in India’s political and economic landscape. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), with Modi at its helm, promised sweeping economic reforms, a relentless fight against corruption, and the revival of the middle class’s aspirations. These promises resonated deeply with millions of Indians who hoped for relief from inflation, unemployment, and the dominance of entrenched elites. However, a decade later, as Modi campaigns for a rare third term, the economic picture presents a stark contrast to those early hopes. According to a recent study by the World Inequality Lab (WIL), income and wealth inequality in India have reached alarming levels, surpassing those in Brazil, South Africa, and even the United States.

The study, titled The Rise of the Billionaire Raj, offers a striking comparison between current levels of inequality in India and those during British colonial rule. Co-authored by Nitin Kumar Bharti from NYU Abu Dhabi, Lucas Chancel from Harvard Kennedy School, and Thomas Piketty and Anmol Somanchi from the Paris School of Economics, the research reveals a troubling trend. In the 1930s, under British rule, the richest 1% of Indians controlled just over 20% of the national income. This figure dropped during World War II and remained around 12.5% at the time of India’s independence in 1947. Under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s socialist policies in the 1960s and 70s, this share plummeted to about 6% by 1982.

However, the liberalization of India’s economy in 1991 marked the beginning of a significant shift. By the early 2000s, the top 1% controlled more than 15% of the national income. By the time Modi took office in 2014, this figure had crossed 20%, and by 2022-2023, it had soared to an unprecedented 22.6%. While India’s GDP continues to grow at over 7% annually, this rapid economic expansion seems to exacerbate the inequality, creating a scenario where the rich are getting richer at an unprecedented pace.

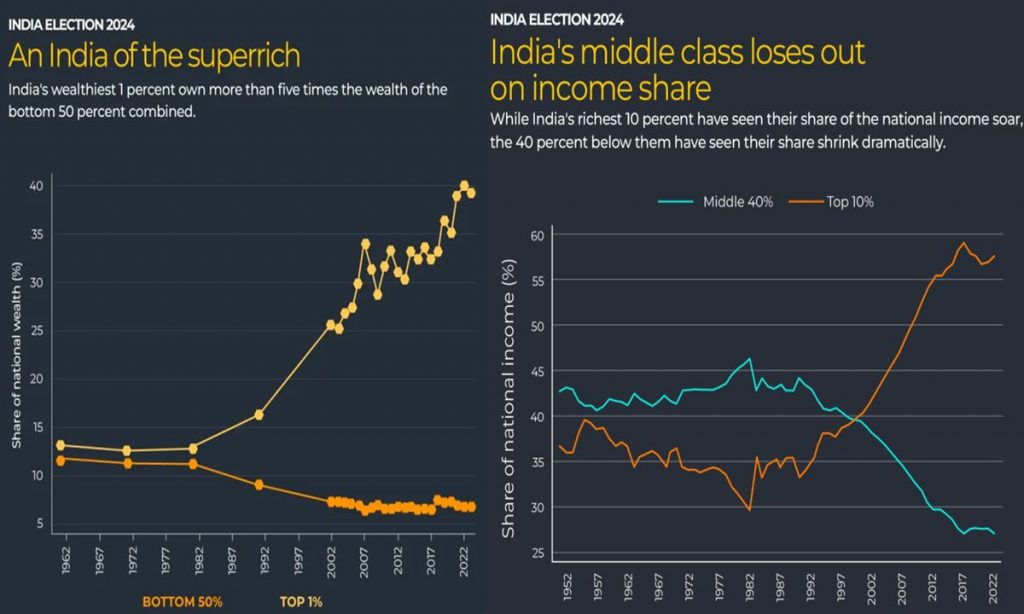

If the income inequality in India is alarming, the disparity in wealth distribution is even more striking. The WIL study indicates that in 1961, the top 1% of Indians controlled less than 15% of the nation’s wealth. Today, their share exceeds 40%. The wealth of India’s richest remained relatively stable before the economic liberalization of 1991 but surged dramatically afterward, crossing 20% by the turn of the century. During Modi’s tenure, this figure jumped from 30-35% to over 40%.

As Modi campaigns for re-election, the mounting inequality suggests that many Indians are struggling as much, if not more, than they were a decade ago. Development economist Jayati Ghosh, a professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, notes that the electorate concerned with economic issues in 2014, such as corruption and unemployment, now faces a regime focused on religious polarization rather than economic reform.

The WIL study highlights a significant squeeze on India’s middle class. The top 10% now control almost 60% of the national income, up from 30% in 1982. This concentration of wealth has primarily come at the expense of the middle 40%, whose share of national income has plummeted from above 45% in the early 1980s to about 27% in 2022. The poorest 50% have also seen their share fall from above 23% to 15% during the same period.

Rishabh Kumar, an assistant professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts Boston, explains that privatization and globalization have favored those with higher education levels, traditionally accessible to the wealthy and upper-caste communities. Consequently, the middle class faces diminished prospects for upward mobility, with most failing to achieve even the national average income.

The opulence of India’s wealthiest was on full display during the pre-wedding celebrations of Anant Ambani, son of Asia’s richest man Mukesh Ambani. The $120 million extravaganza included a private concert by Rihanna and attendees like Mark Zuckerberg and Ivanka Trump, highlighting the stark contrast between the ultra-rich and the rest of the country. In 1991, India had just one dollar billionaire; by 2024, this number had skyrocketed to 271, making India third only to China and the US in the number of billionaires.

The wealth of Indian billionaires grew by more than 280% between 2014 and 2022, vastly outpacing the 27.8% growth in national income. Meanwhile, a quarter of the world’s undernourished population resides in India, and millions experience severe food insecurity and chronic hunger. The WIL report captures other indicators of India’s sharpening inequality, too: just 1% of Indians take 45% of all flights in the country; only 2.6% of Indians invest in mutual funds; and 6.5% of Indians are responsible for 45% of all digital payments. The divide extends to the dining table, with 5% of users accounting for a third of all orders on Zomato, India’s largest food delivery app.

The deepening inequality in India is partly rooted in structural issues. Despite significant economic growth, nearly half of India’s workforce remains in agriculture, a sector that has seen limited productivity improvements. The education system, favoring elite tertiary education over broader educational needs, has further entrenched inequality.

Recent policy decisions have also exacerbated the divide. Modi’s demonetization in 2016, the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) in 2017, and the harsh COVID-19 lockdown in 2020 disproportionately affected the informal sector, which constitutes a significant portion of India’s workforce. These measures have disrupted livelihoods and employment, particularly among the poor and middle class.

Demonetization, announced in 2016, aimed to curb black money and counterfeit currency but ended up severely impacting small savings and liquidity in the informal sector. The sudden withdrawal of high-denomination notes caused widespread chaos, with many small businesses and daily wage workers facing immediate financial hardship. The move crippled vast swaths of India’s small-scale industries, which rely heavily on cash transactions.

The introduction of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) in July 2017, intended to simplify the tax structure, also had unintended consequences. The GST regime created compliance challenges for small businesses and informal sector enterprises, many of which were ill-prepared for the transition to a digital tax system. The complexity and burden of GST compliance led to business closures and job losses, exacerbating economic disparities.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent nationwide lockdown in the spring of 2020 delivered another severe blow to India’s informal sector. The lockdown, imposed to contain the spread of the virus, resulted in millions of migrant workers losing their jobs and being forced to return to their villages. The sudden cessation of economic activity caused widespread distress, particularly among those with precarious employment in the informal economy.

The WIL study observed that the Indian income tax system might be regressive when viewed from the perspective of net wealth. In essence, wealthier individuals pay less in taxes as a proportion of their assets compared to the less wealthy. This regressive taxation exacerbates income and wealth inequality, creating an environment where the rich accumulate more wealth while the poor struggle to meet basic needs.

To address this growing inequality, the authors of the WIL study advocate for implementing a “super tax” on billionaires and multimillionaires. This additional tax on the wealthiest individuals could serve as a tool to combat inequality. The study also recommends restructuring the tax system to include both income and wealth taxes, ensuring that the wealthier segments of society contribute their fair share.

According to Bharti, one of the co-authors of the WIL study, the solution to inequality lies in education. He emphasizes the need for India to create the right set of human capital tailored to the jobs that need to be created. By aligning the education system with market demands, India can ensure that its workforce is better prepared for the evolving economic landscape.

Currently, India’s education system is skewed towards the elite, with limited access to quality education for the broader population. This disparity in educational opportunities perpetuates economic inequality, as those with higher education levels and better skills secure well-paying jobs, while the majority remain trapped in low-paying, precarious employment.

The Communist Party of India (CPI), though a small political force, has proposed measures to address economic inequality in its 2024 election manifesto. The CPI advocates for the introduction of wealth and inheritance taxes to create a more equal and just economy. The party’s general secretary, D. Raja, has criticized the BJP’s rule for unprecedented wealth concentration at the top while pushing the poor into destitution.

The main opposition party, Congress, has also pledged to reset economic policies and tackle the BJP’s legacy of “job-loss growth.” However, Congress has been cautious about wealth redistribution plans, particularly after Modi attacked the party, suggesting it wanted to take wealth from Hindu families to give it to Muslims.

Political commentator Asim Ali pointed out that the relative absence of robust opposition movements has allowed the BJP to evade accountability on economic issues. The BJP’s focus on Hindu majoritarian narratives and religious polarization has diverted attention from pressing economic concerns. This strategy has helped the ruling party maintain its voter base despite the growing economic inequality.

However, the mounting inequality cannot be ignored indefinitely. As the gap between the rich and the poor continues to widen, the economic disenfranchisement of the majority might eventually lead to political unrest. The challenge for India’s opposition parties is to build a cohesive narrative that addresses the economic realities faced by millions of Indians while countering the BJP’s divisive politics.

The deepening inequality in India is unsustainable in the long run. An economy where a small fraction of the population controls a disproportionate share of wealth and income cannot achieve sustainable growth. The concentration of wealth among the top 1% stifles economic opportunities for the majority, leading to reduced social mobility and increased social tensions.

For India to achieve equitable growth, structural reforms are necessary. These reforms should focus on improving access to quality education, healthcare, and social services for all segments of the population. Policies aimed at boosting employment in sectors beyond agriculture and ensuring fair wages are critical to reducing economic disparities.

Additionally, progressive taxation policies that target wealth accumulation can help redistribute wealth more equitably. Implementing wealth and inheritance taxes, as proposed by some political parties, could provide the government with the resources needed to invest in social infrastructure and public services.

India’s rising inequality is not an isolated phenomenon. Many countries around the world are grappling with similar challenges as globalization and technological advancements create new economic dynamics. However, countries like the Scandinavian nations have managed to maintain relatively low levels of inequality through robust welfare systems, progressive taxation, and inclusive economic policies.

India can draw lessons from these countries by adopting policies that promote social equity and economic inclusion. Strengthening social safety nets, ensuring universal access to quality education and healthcare, and creating an enabling environment for small and medium enterprises can help bridge the inequality gap.

As India heads into the next election, the issue of inequality is likely to remain a significant political and social flashpoint. The country’s future economic stability and social cohesion depend on addressing this widening gap. While Modi’s government has presided over significant economic growth, the benefits of this growth have been unevenly distributed, leading to greater income and wealth disparities.

The solution lies in comprehensive and inclusive economic policies that prioritize the well-being of all citizens, not just the elite. By focusing on education, progressive taxation, and social welfare, India can work towards a more equitable society where economic opportunities are accessible to everyone. The path to reducing inequality is challenging, but it is essential for creating a just and prosperous India for future generations.